Amelia Boggess Theory Review: The Brain and Mind in Learning

Theory Review: The Brain and Mind in Learning

Amelia Boggess

Department of Educational Studies, Ball State University

EDAC 635: Strategies for Teaching Adults

Dr. Bo Chang

February 21, 2021

For educators, there are seemingly incalculable channels of theoretical studies available to assist in understanding the learner and the learning process. Among one of the most valuable of these channels is the relationship between the brain and mind and its impact on learning. MacKeracher (2004) states, “To understand learning fully, we need to consider cognitive aspects of learning and explore the relationship between brain and mind” (p. 92). The theories and research available within this context are vast in number. However, for the purpose of application to the education of adult learners, this theory review will focus on the following three theories: the triune brain, brain-based learning, and cognitive styles.

Main Theoretical Points

The Triune Brain

To understand the relationship between the brain and mind, let us begin with exploring the brain itself. MacKerarcher suggests that the “easiest way to understand how the brain functions in learning is to view it as having three levels, each having its own form of memory, its own way of gathering information, its own sense of space and time, its own intelligence, and its own means for controlling behaviour” (2004, p. 95). Paul MacLean introduced this theory of the triune brain in the 1960s (Baars & Gage, 2010, p. 1.1). This theory states that the brian is composed of three parts - the reptilian brain, which regulates the basic elements of survival, the limbic system (or paleomammalian brain), which regulates emotional experiences, and the neocortex (or neomammalian brain), which “ allows the interpretation of events and decisions made thoughtfully” (Arboccó de los Heros, 2016, p. 1).

Figure 13.1. The triune brain: orange represents neocortex, green is the mammalian brain, and yellow is the reptilian brain. From 1.1 The Triune Brain: 1.1 Emotion, by Baars, B. J., & Gage, N. M., 2010 https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/neuroscience/triune-brain

The reptilian brain can “suppress or augment stimuli [...] on the basis of individual needs for survival and safety, specifically for the primitive emotions driving the basic functions” (MacKeracher, 2004, p. 95). Memory in the reptilian brain solely relates to survival and threat; it is “impervious to learning as we understand it” (MacKeracher, 2004, p. 96). This concept is supported by Baars & Gage, “This brain layer does not learn very well from experience, but is inclined to repeat instinctual behaviors over and over in a fixed way” (2010, 1.1).

The limbic system “has a major role in human emotion” (Baars & Gage, 2010, 1.1). All stimuli must first go through the limbic system before arriving at the neocortex, where patterns and meanings are identified. “The limbic system judges all experiences on the basis of pain and pleasure” and “[new] learning is mostly restricted to expanding existing values and registering new experiences” (MacKeracher, 2004, p. 96).

The neocortex houses the cerebral cortex (the two cerebral hemispheres) which are responsible for “virtually all learning we are concerned with in formal education and informal learning” (MacKeracher, 2004, p. 96). All stimuli must first go through the first two portions of the brain in order to arrive at the neocortex; “it is dependent on the lower levels of the brain to pass on information, yield control over various activities, and keep the entire system activated” (MacKerarcher, 2004, p. 97). One of the most significant elements to learning within the intricate system of the triune brain is the process of down-shifting. “Whenever sensory stimuli implying a threat to the individual are received… the brain will downshift, taking direct control over cognitive functions away from the neo-cortex and giving it to the limbic system or the reticular activating system” (MacKeracher, 2004, pp. 96-97).

While “some aspects of the triune brian theory have been controversial” (Baars & Gage, 2010, 1.1), it can be incredibly useful for an educator to consider the implications.

Brain-Based Learning

Brain-based learning theory is founded on “learning that is relevant based on the natural functions of the brain, where students can learn significantly with brains preparing students to store, process, and retrieve information” (Handayani & Corebima, 2017, p. 2); this theory is the cooperation of research from “various fields such as neuroscience, biology, and psychology” (Handayani & Corebima, 2017, p. 2).

As an educator, it is beneficial to understand the concepts of brain-based learning in order “to ensure that our facilitating strategies do not violate [the rules that control and constrain the brain’s activities]” (MacKerarcher, 2004, p.100, as cited in Caine & Cain, 1991).

Mackeracher introduces five principles to brain-based learning, as well as key considerations to the educator facilitating learning based on these principles.

The brain is always doing many things at one time.

To learn, the brain needs to be processing information.

The brain allows for both conscious and out-of-conscious learning.

Whatever we learn is embedded in the context in which we learn it.

All facilitating activities have an effect on both cerebral hemispheres; however, some have a stronger effect on one hemisphere than the other.

(MacKeracher, 2004, pp. 100-102)

There are many important things to be gleaned from these principles. First, when a learner is consciously learning, their brain is also continuing its subconscious work of monitoring and regulating the body, its functions, and even the concerns of daily life. An educator should be aware that these “out-of-awareness concerns may become of greater concern to the learner than the task of learning” (MacKerarcher, 2004, p. 100). This concept ties to the idea of the triune brain downshifting and being unable to learn.

Next, if you have ever sat through a lecture only to find yourself noticing the piece of dust on the table in front of you, thinking about the temperature of the room, or thinking about a new way to cook your favorite protein later, you are not alone. While a lecture can have its benefits, the brain needs not only to receive the information, but to be able to process it. “Good facilitation should be understood as a process of orchestrating the learners’ experiences through providing a variety of activities and resources” (MacKeracher, 2004, p. 100).

It’s also important to note that each learner makes sense of their own experiences in the learning process. It is not just through the direct instruction, but rather the entire experience (both conscious and unconscious) that learning is composed of. “Learners need to learn how to become aware of, and benefit from, out-of-conscious learning through processing the total experience and not just the information presented by the facilitator” (MacKerarcher, 2004, p. 100).

Because our brain learns in context, it is no surprise that adult education standards for curricula have shifted over the years putting heavy emphasis on contextualizing all learning - not only for immediate application in life, which is an assumption of adult learning, but also because it is a brain-based strategy for learning. “Facilitating success depends on having learners use their senses and immersing learners in many different, complex, and interactive experiences over time” (MacKeracher, 2004, p. 102).

Additionally, despite theories that suggest people are left-brained or right-brained, studies have proven that we use both brain hemispheres for all forms of learning, though people may have inclination or a strength seemingly one over the other. That being said, an effective facilitator will utilize facilitation/learning strategies that engage both hemispheres of the brian, such as activities depending on time-ordered sequence (left hemisphere) and activities depending on visual or nonverbal materials (right hemisphere) (MacKerarcher, 2004, p.102).

Another development from brain-based learning research has been the creation of several models of learning. Examples of these are the aptly named Brain-Based Learning (BBL) and the Whole Brain Teaching (WBT) models. “BBL is learning that is based on the idea that each part of the brain has specific functions that can be optimized in the learning process” and “WBT is learning with instructional approaches derived from neurolinguistic picture based on the right and left brain function” (Handayani & Corebima, 2017, p. 2). In these models, educators are expected to create a fun learning system based on the systems of the brain.

For example, the BBL model includes the following pieces: pre-exposure, preparation, initiation and acquisitions, elaboration, incubation and inserting a memory, verification and checking conviction, celebration and integration (Handayani & Corebima, 2017, p. 4). Each of these pieces links to a different system in the brain such as the cerebellum (ex: movement, body gesture, balance), cerebral cortex (ex: thinking, speaking, planning, analysis), frontal lobe (social behavior), limbic system (memory and emotion), and prefrontal cortex (happiness and comfort) (Handayani & Corebima, 2017, pp. 4-5).

In studying the principles of brain-based learning and the increasing number of instructional models based on this theory, educators can add to their teaching toolkit with knowledge leading to more impactful learning. “In learning, more learning activities will connect more nerves in the brain” (Handayani & Corebima, 2017, pp. 2).

Cognitive Styles

“The brain represents the physical side of mental functioning; the mind represents the cognitive side” (MacKeracher, 2004, p.71). As this theory review has spent considerable time on the physical brain, we must now turn our attention to the mind by exploring the theory of cognitive styles.

Cognitive styles refer to an individual’s characteristic approach to organizing and processing information (Tennant, 2006, p. 79). In education, this term is commonly used alongside learning style. Cognitive styles are typically referred to as opposite ends of a spectrum. For example, a person is convergent or divergent, reflective or impulsive, field dependent or independent, analytic or holistic. In these instances, “both poles of the continuum are equally valuable, each having adaptive qualities in different contexts” (MacKeracher, 2004, p. 73). For the purpose of conciseness, the two cognitive styles that will be used as examples in this section are field dependence/independence and analytic/holistic cognitive styles.

MacKeracher (2004) discusses holistic and analytic cognitive styles in terms of three basic cognitive processes: perception strategies, memory strategies, and thinking strategies. Perception strategies involve pattern recognition and attention. Memory strategies include information being “stored or represented in memory, the manner in which information is organized, and the strategies involved in retrieving the stored information” (p.106). Thinking refers to classifying, reasoning, and inferring (p.110). Within each of these processes, “specific paired cognitive strategies are viewed as contributing to two basic cognitive styles; an analytic style and a holistic style” (p.73). MacKeracher’s Figure 4.1 provides a fantastic summary of the two cognitive styles.

Figure 4.1 Summary of perception, memory, and thinking differences in cognitive styles. Analytic and Holistic Cognitive Styles. From Making sense of adult learning (2nd ed.) (p.75), by Dorothy MacKeracher, 2004. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

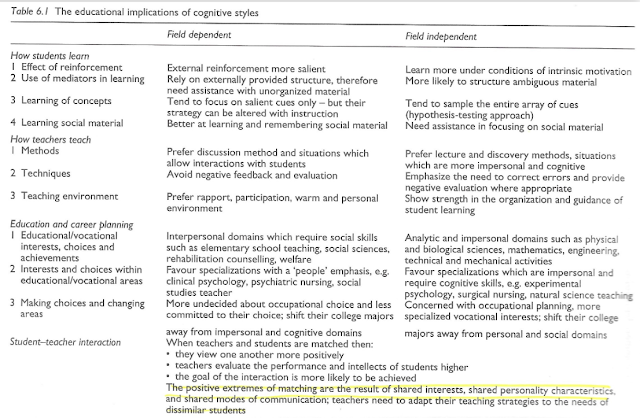

Figure 4.1 Summary of perception, memory, and thinking differences in cognitive styles. Analytic and Holistic Cognitive Styles. From Making sense of adult learning (2nd ed.) (p.75), by Dorothy MacKeracher, 2004. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.Like the analytic and holistic cognitive styles, concepts of field dependence and field independence refer to two ends of a cognitive spectrum where “the individual differences in the influence of context in making perceptual judgements” (Tennant, 2006, p. 80). Tennant (2006) provides a concise summary detailing the educational implications of each of these cognitive styles in Figure 6.1.

Figure 6.1 Field Dependent/Independent. The educational implications of cognitive styles. From Psychology and Adult Learning (p. 82), by Mark Tennant, 2006. Routledge.

“Most adult learners may be capable of using the cognitive processes that serve [both styles], but individuals tend to prefer one over the other” (MacKeracher, 2004, p.75). Wherever an individual may fall on the spectrum between analytical/holistic or field independent-dependent cognitive styles, the research does suggest that “cognitive styles are unalterable” (Tennant, 2006, p. 83). MacKerarcher (2004) states, “Cognitive styles are assumed to be stable and an integral part of personality” (p. 112). Because of this, educators will benefit greatly from learning about their students’ cognitive styles, and presenting information in a “variety of perceptual modes: visual, auditory, kinesthetic, and verbal” (p. 112). The implications of cognitive styles do not stop with how an educator facilitates learning in the classroom, but should extend to how an educator assesses learning as well (p.113).

Applications

There many ways the theories of the triune brain, brain-based learning, and cognitive styles may be put into practice.

Regarding the triune brain theory - that an individual may be unable to learn because of down-shifting (perhaps due to trauma, or circumstances outside or inside the learning environment) can have significant impact on how an educator may go about facilitating learning. “When down-shifting occurs, self-preservation becomes more important than learning and the cerebral hemispheres are put on hold. To reactivate the learning process, the lowest two levels must be satisfied that the threat to self has been resolved” (MacKeracher, 2004, p. 97). This knowledge, as well as how to alleviate the threat, can be an incredibly useful tool for practitioners - particularly those working with at-risk populations. By studying the theory of the triune brain, an educator can then take the steps necessary to obtaining training and skills to help alleviate feelings of threat.

In terms of my own experience teaching adult English as a Second Lanaguage (ESL) learners, I have encountered students who were unable to learn because at that very moment riots were going on in the streets of their Venezeulan neighborhood where their families lived; I’ve also had students who were facing the fear of deportation and seen first hand how these immediate fears for their safety inhibited their learning. Though I was able to work with them, and at times that meant giving them space to deal or cope with an issue before returning to learning, had I been aware of the theory of the triune brain, the skills I would have obtained from researching strategies would have helped me, help them.

Likewise, exposure to the the principles of brain-based learning and cognitive styles (which go hand-in-hand) can have a crucial impact on educators (and their learners). As educators learn about these theories, they begin to understand not only the existence and preference for differentiated instruction including verbal, written, auditory, and kinesthetic elements, but also how incorporating these elements is linked to they way in which their learners learn. For example, I once took a class on mathematical probability where the teacher lectured the entire time, and assigned homework from a textbook. Despite having a proclivity for math in my previous schooling, this class confounded me. Had he contextualize the lessons and given ample activities for students that included a visual, kinesthetic, and discussion elements, I may have began to understand the concept a little better. Certainly, I would have (a) felt differently about the class, leading to a more positive environment and emotions (hello limbic system!), and (b) understood the concept from a practical sense (contextualized). By engaging the class in a variety of activities, students would have had the opportunity to engage with the content in ways that were more compatible with their cognitive styles.

Reflection

Highlights

The most significant parts of this assignment had to do with sifting through the information - there are so many applicable, meaningful, and interesting theories on the brain and mind in learning. The final three theories that I landed on were ones that I found immediately relevant to the experiences I have had in learning and teaching. The most significant part of this assignment was my time spent learning about the triune brain; it brought up many inspiring questions for future study in regards to at-risk populations, trauma and its impact on learning, and well as what I as an educator can do when armed with this knowledge. Additionally, learning about brain-based learning helped for me to contextualize teaching strategies and learning models I have already put into place; essentially, this reinforced the why of what I do and how it impacts my learners.

Process

For this assignment, I began by reading MacKeracher’s chapter five, The Brain and Mind in Learning. I picked out 6 topics that I wanted to research and explore. Then, I researched published articles and narrowed down my topics to the three listed. I re-read the section for each topic in MacKeracher, and then read the article or chapter I had found on the same topic. This process worked well for me. However, I wasted much time in researching topics and articles that I did not use for this review. I would recommend narrowing the topics down before doing the research.

Table 1. Summary of the theoretical ideas

References:

Arboccó de los Heros, M. (2016). Neuroscience, education and mental health. Propósitos y Representaciones, 4(1), 327-362. https://doi.org/10.20511/pyr2016.v4n1.92

Baars, B. J., & Gage, N. M. (2010). 1.1 Emotion. In Triune Brain. https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/neuroscience/triune-brain

Handayani, B. S., & Corebima, A. D. (2017). Model brain based learning (BBL) and whole brain teaching (WBT) in learning. International Journal of Science and Applied Science: Conference Series, 1(2), 153-161. https://doi.org/10.20961/ijsascs.v1i2.5142

MacKeracher, D. (2004). Making sense of adult learning (2nd ed.). Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Tennant, M. (2006). Learning Styles. In Psychology and Adult Learning (pp. 79–92). Routledge.

Hi Amelia,

ReplyDeleteThanks for sharing your breakdown of the brain and mind in learning. I think you did a great job connecting how the brain works and how we can connect that to creating and facilitating learning activities. I also appreciated your use of visual aids in your paper. Great job!

Thanks, Jason! I almost didn't include the visuals, but in my paper I discuss how presenting things in more than way is a best practice - so I thought I would follow my own advice! I appreciate your comment and compliments!

DeleteAmelia,

ReplyDeleteI really learned a lot from your post. I could relate when you mentioned that students may be sitting in a lecture and thinking about the dust on the table or what they are going to have for dinner. This emphasizes the need for engagement and the brain's role in that - both the learner and the facilitator have a role in this. As you mentioned, we as facilitators can employ strategies to activate different parts of learners' brains while as learners, we have to find ways to stay engaged and find ways that work for us to stay focused. There was a lot of great information presented here, thanks for sharing!

Mady

Hi Mady,

DeleteThanks for your comment! I am glad you were able to learn from this post. Now, I find myself wondering how we can utilize these concepts and apply them to the remote classroom that so many of us are in. I've definitely got some food for thought myself.

Thanks again for commenting!

Hi Amelia,

ReplyDeleteI enjoyed reading your review. I am glad that you mentioned that the stories we have all heard about people being strictly "left-brained" or "right-brained" are not scientifically accurate as all learners are capable of using both sides of the brain on a learning task. During my research for my own theory review, one of the articles I read mentioned that scientists have documented that people generally breathe through one nostril for about 3 hours until the tissue in that nostril becomes slightly engorged, and then we switch to the other side. The nostril we breathe through affects which brain hemisphere is dominant at that particular time. This can partly explain why people may be better at certain tasks at certain times of the day and then may struggle with a similar task at a later time in that same day. I had never heard that before, and I found it really interesting. I didn't focus on left-brain vs. right-brain as one of the topics in my review, so I didn't include that little nugget in my theory review, but I thought you might find it interesting since you did discuss left-brain and right-brain dominance.

Nice work!